So, would you watch a 13-hour film?

That’s the inevitable first question that crops up in any discussion of Jacques Rivette’s 1971 opus Out 1: Noli Me Tangere. But that run time is just one element of a glorious mystique that has built up around this masterwork. The release of a brand new Rivette Collection box set (by Kino Lorber in the U.S., and Arrow Video in the U.K.) with Noli Me Tangere (plus its shorter version, the 4-hour Out 1: Spectre) brings the film to the masses, and demystifies one of cinema’s holy grails. It was not a lost film, rather a film that was difficult to find, its history plagued by bouts of obscurity. That won’t be happening again. Originally conceived as a television series, Rivette eventually made it into a 13-hour feature with an eight-episode structure. Rivette drew inspiration from early serials like Feuillade’s Les Vampyres (1915), which is similarly compartmentalized, yet shown in its entirety. He called it Out 1 to show his refusal to be ‘in’; it would ultimately become too obscure to be anywhere near ‘in’. Its blend of length, structure and thematic depth fuelled a cult following; seeing Out 1 became a badge of honour for cinephiles. Now, it’s open to all; given that the film playfully mocks the leftist revolutions of 1968, it’s another layer of irony to be added to this elusive work.

The enigma of Out 1 only deepens when trying to explains what it’s all about. There are characters, but the story in which they’re involved evolves and shifts about very readily, even diminishing in importance from time to time as we switch from one location and one set of characters to another. The film centres on two theatre groups in rehearsal. Each group is rehearsing an Aeschylus play; one’s doing Seven Against Thebes, the other Prometheus Bound. Like a hangover from Rivette’s previous film L’amour fou, we watch the groups engage in prolonged exploratory exercises built on spontaneity, a method favoured by many theatre groups at the time. From one group performing yoga-aping feats with limbs and bottoms, we cut to the other group lumbering and squealing around a dummy, like the apes reacting to the monolith in 2001. As with these actors, there’s a playful freedom to Out 1 that makes the whole endeavour seem quite unpredictable. Unbound to expectation, Rivette captures this latter rehearsal in an unbroken shot that continues for well over half an hour. Plot will come later, as the links between the two groups are revealed to be more personal than a shared playwright. In the meantime, we’re propelled into the workings of these groups, and relationships are laid down that will drive the narrative on when it actually arrives.

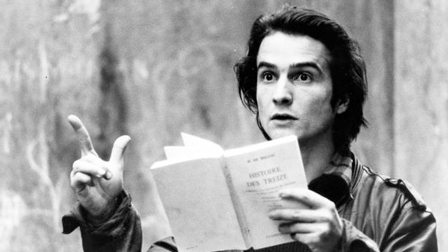

Also in this mix are two con artists, also operating separately from each other. The most recognisable face in the film is that of Jean-Pierre Léaud as con man Colin. At this stage, he had not yet finished playing Antoine Doinel for Truffaut, and is just one of many ways Out 1 ties into film history. The film is riddled with faces and names who defined, and would continue to define, French cinema. Michael Lonsdale became a renowned character actor both in France and beyond. Bernadette Lafont would be known before and after for her work with director Claude Chabrol. Bulle Ogier and Juliet Berto would star in Rivette’s Céline and Julie Go Boating, before forging successful partnerships with Rivette and Jean-Luc Godard respectively. And so on. Out 1 teems with the energy of these young actors, who never baulk at the film’s relative lack of narrative. In fact, they embrace it. The narrative flexibility allows them to create memorable characters and moments. One of the defining scenes of Out 1 sees Colin walking down a Parisian street reciting a passage from Lewis Carroll’s The Hunting of the Snark, which he believes contains a clue to the theatre groups’ activities. There is a determination to Léaud’s performance that borders on intimidating, especially next to the more naturalistic work by members of the theatre troupes. Rivette’s greatest feat is to have created such a hypnotizing journey from so many disparate elements. The disparities are manyfold, but we’re willing to forgive the odd appearance by a boom mike or a self-conscious extra when the work holds together as a whole so well. It’s like the most cerebral soap opera you could possibly imagine.

Berto plays conwoman Frédérique in Out 1; both she and Colin get mixed up with the theatrical groups by way of curiosity. Both are fascinated by rumours and suggestions of a group (Theatrical? Political? Or otherwise?) called ‘The Thirteen’. It’s a direct reference to Balzac’s Comédie Humaine, to which Out 1 is hugely indebted. It is the primary literary link in a work that is generously suffused with cultural references. The intertextuality at play throughout the film is a treasure trove. From Balzac to Cayette, to Carroll, to New Wave directors, to Rivette’s own filmography, this is full of material ripe for critical analysis. A most delicious example occurs when Éric Rohmer, another literary-minded purveyor of film serials (Six Moral Tales) turns up for a cameo as a Balzac expert approached by Colin for information. It’s no spoiler to say that the mystery of ‘the Thirteen’ is not worthy of either Colin and Frédérique’s efforts; the former seems quite disappointed in the louche organization of their nominal hideout ‘The Corner of Chance’ (a dive run by Ogier’s Pauline). Yet Out 1 is all about that search for belonging. Each part of Out 1 is necessary, and the con artists want to feel needed and necessary, too. Any time either group comes under threat (which is often), the members panic. Out 1 is about a sense of community and definition within a group. Colin’s con act involves him playing a deaf-mute; out of a strange mix of loneliness, curiosity and boredom, he suddenly feels a need to be heard by others. At least two significant characters in Out 1 are only referred to, and never viewed onscreen. Though they prove important through their offscreen actions, there is a pervading sense that these groups could carry on just as well without them. These men may not be islands, but the links that bind them to others are threatened by the men’s absence from proceedings.

The episodic format of Out 1 has worked before and since (Think of Kieslowski’s Dekalog or, more recently, Dumont’s P’Tit Quinquin). Screenings of the film, from its initial presentations up to recent showings in New York, London, Dublin and other cities, tend to spread the film across two days, with four episodes each day. You might say the home entertainment release of Out 1 came at just the right time; with binge-watching becoming the new ‘Tune in next week’, the freedom permitted by the DVDs is a wonderful thing. Out 1’s episodic structure works in tandem with its thematic complexity and richness. It could only be accentuated by the ability to pause and rewind. Rivette couldn’t have seen the age of boxsets and binge-watches coming, but the fact that he survived to see the day (He died in January 2016, aged 87) may well have amused him. This is the format his chef d’oeuvre has been waiting for.

The Jacques Rivette Collection, featuring Out 1: Noli Me Tangere, Out 1: Spectre and three other Rivette films, Duelle (une quarantaine), Noroît (une vengeance) and Merry-Go-Round, is now available from Arrow Video.